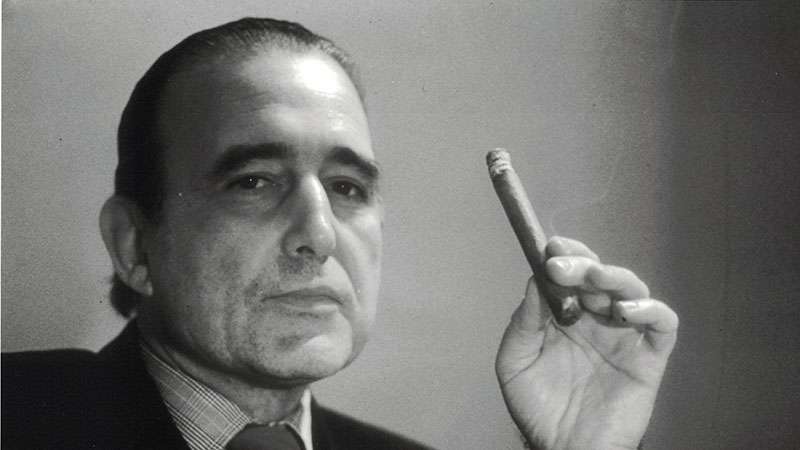

When Reiner Moritz, now world-renowned for his arts programs, was working for Leo Kirch’s Beta Film in Munich, he was a chain smoker. One day Reiner couldn’t smoke all day; the two were driving to Nuremberg and Kirch did not allow smoking in his car. And from then on he didn’t smoke for 10 years. But when the violinist Isaac Stern, for whom he did television work, offered him a top Cuban cigar (Monte Cristo No. 3), he couldn’t resist. Ever since, he has “enjoyed a good cigar after a meal, but not regularly, and no longer inhaling,” he explained.

Embracing quality product has been Moritz’s raison d’etre. This is why he’s always been attracted to arts programs, which he produced and co-produced first under the RM Arts and Music label and most recently with Poorhouse International, based in London.

Over e-mail and for lunch at his Cannes residence during MIPCOM, VideoAge also discussed the business model of arts program productions with Moritz.

About Moritz’s famed luncheons, Tarmo Kivikallio of Finland’s YLE commented: “YLE has bought a lot of documentaries and classic programs from him, and many times at MIP-TV or MIPCOM I have had the pleasure of joining his lunch meetings on the last day of the event. Actually, those meetings are more pleasure than business and Dr. Moritz seems to enjoy this tradition.”

“Arts programming doesn’t necessarily come in cheaply,” Moritz said in a subsequent interview. “Although a performance is there, a multi-camera shoot, sound recording and post-production cost money. You also have to compensate for seat loss and house fees. Major performances used to cost between U.S.$1 million and $1.5 million to record.”

He further explained: “[During] the golden age of arts television in the ’60s and ’70s — when even commercial broadcasters like ITV in the U.K. [transmitted arts shows] — usually the local public broadcaster would bear the brunt of [the production costs]. Distributors would put up a minimum guarantee and hopefully make some money. [Later on,] laser disc and DVD helped. Artists were normally bought out.

“Today, most arts programming only exists because of foundations and grants and most institutions have contracts, which either include the artists or give them a percentage. [As for us, nowadays we] only deal with theme channels, but Sky U.K., Sky Germany, Skyarts New Zealand and Foxtel Arts Australia keep us going.”

Moritz has received a number of honors for his expansive artistic body of work, and in 1995 he was elevated to the rank of Officier des l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres at MIPCOM in honor of the 25th anniversary of RM. In 1997, the French television festival FIPA had a retrospective of Moritz’s films.

Moritz began his career as a journalist, writing for the Hannoversche Presse in his native Hannover, Germany. Soon after, he moved to the national daily newspaper Die Welt where he remained until 1961. Then, at the age of 23, he joined Munich’s Beta Film, then a five-year-old company founded by Leo Kirch.

Moritz entered the entertainment business by accident. As he recalled, “I was looking for some writing job and ended up selecting short films for a daily slot the young Kirch had clinched from [TV station] Hessisches Werbefernsehen.”

Moritz also remembered how difficult it was in those early days, especially “to persuade Leo Kirch to accept the sales prices I negotiated, because he always wanted more.”

In 1970, when Moritz left Kirch, he founded RM Productions in Munich with the Hamburg-based Polytel International as the majority shareholder. In 1976, he split from the company to found RM Arts and Music — also in Munich — with Kirch as majority shareholder.

Subsequently, RM became a full subsidiary of the Kirch Gruppe, which had evolved from Sirius in 1956 into Beta Film in 1959, followed by Taurus. When Kirch Gruppe collapsed in 2002, the liquidators sold RM Arts and Music to Arthaus Musik, while Moritz went on to create Poorhouse International, a London-registered Munich-based company a year later. “[I] had my own company again,” he said, explaining, “The name derived from the Massachusetts’ summer house of Curt Davis, formerly VP of Programming for [the New York City-based] ARTS, later A&E.

“It was one of the old buildings in New Haven [and later on it was used] to house poor people. Davis also called his production company Poorhouse and when he died, I organized a scholarship in his name and his widow allowed me to use it.”

Poorhouse concentrates on major music documentaries and represents selected producers. In 2013, Moritz was commissioned to do a documentary titled Dance on Screen, exploring the interaction of film, television and dance.

On his frequent commutes to London, which at times are “weekly, but mostly monthly,” Moritz explained, “I have always held that London is central to our business, and have had connections [there] since 1962. From 1983 to 2002 I had a distribution company in London, RM Associates, which closed because of the Kirch Gruppe failure, as they had 51 percent of the voting rights.”

During the early years of his career in program distribution, Moritz encouraged the creation of trade shows. This need evolved from his participation in the ’60s at trade events such as Prix Italia, the RAI sponsored radio and TV festival. That was created in Italy in 1948, but did not include program sales facilities. “I won twice with [film director] Tony Palmer’s profiles of composers Benjamin Britten (1967) and William Walton (1980).”

His first market was MIFED in Milan. “I have always attended MIFED so long as EBU members went there, who were my clients. We even won the Perla Award for our film on Expressionism. MIFED was a very pleasurable event, well organized and with good viewing facilities. I very much regret that MIFED was [closed],” he said.

Moritz’s second market was MIP-TV, which was first held in Lyon, France in 1963 and two years later moved to Cannes because “the mayor of Lyon did not want it,” recalled Moritz.

This is how he remembered it: “At the [market’s] winding-up party, the then- mayor of Lyon Louis Pradel (nicknamed Zizi béton, because he had cut the city in half with the Paris-Marseille motorway) leaned over to me and said: ‘You see, there are not so many people around. I don’t think television has a chance.’ And so MIP moved to Cannes.”

Compared to today’s international TV trade shows, the first MIP was a game of endurance. Recalled Moritz: “MIP was launched in one of the huge halls at the Lyon Trade Fair. Some 200 television executives turned up. [Sellers] had to bring film prints because no other support had yet been invented, and in those days France had no automatic telephone system. So, I spent hours sitting on a staircase near an improvised telephone booth waiting for a call to go through to Stockholm. I had been given a scrap of paper with a four-line synopsis for Ingmar Bergman’s new film, The Silence. As was typical for the director nobody knew much about the plot and it was thanks to somebody on his staff that I knew anything at all. When the call finally came through I bought the trilogy Through A Glass Darkly, Winter Light and The Silence for a million Swedish crowns [about U.S.$1.5 million in today’s money] only to get into a heated argument with my boss, Leo Kirch, who thought I had bought All These Women (in color and a flop) while I had three movies in black and white. Eventually, The Silence passed censorship and Germany was one of the few countries where the movie was shown uncut, as it was a work of art. It became one of the highest grossing titles at the time.”

Moritz first met MIP-TV founder Bernard Chevry in 1962, when Chevry was trying to market a documentary that he produced, and asked Moritz to sell it.

Chevry quickly realized that facilitating the buying and selling of programs could be more profitable than producing them, which Moritz encouraged. At that time the only markets were MIFED in Milan and Prix Italia, which, Moritz said, was the best way to meet broadcasters even though, he recalled, “we were only allowed to talk to the acquisition executives, and we didn’t even know the names of people in charge of programming.”

About Cannes, Moritz recalled: “When the old Palais was still standing and the [adjacent] Blue Bar was an important meeting place during the Cannes Film Festival, I negotiated with [Mexican producer] Gustavo Alatriste for German-speaking rights for his latest film Viridiana by [director] Luis Buñel. Being careful, I asked for and obtained a signed five-point deal on the back of the [Blue Bar’s] menu. The next day, the film won the Palme d´Or. Alatriste first tried to wriggle out of the deal but then stood by his signature. This was in May 1961.”

At times, selling arts TV programs was difficult even in Scandinavia, the biggest consumer of the genre: “Trying to sell a series of Karajan concerts to Finland’s Mainos TV, I failed miserably,” said Moritz. Later, talking to Mainos’ founding president Pentti Hanski, he promised to help. I was invited to their brand new offices in Helsinki where a buffet lunch had been laid out for the office staff. I had been charged to bring the most popular of the series, which was Alexis Weissenberg playing Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto Number 1. We had drinks and a screening after which Pentti asked everybody present whether they would like to see this on their channel. The answer was an overwhelming ‘yes’. I got my series placed, which garnered very good ratings between Christmas and New Year against an popular YLE comedy show, which nobody could have beaten anyway.”

He recalled another funny story. “It must have been 1967 when I was desperate to get some deals with Sweden’s SVT, who were upset because Beta Film had bought up European rights in all important Japanese art-house movies and had them restored. Public service broadcasters at that time preferred to deal at source and didn’t like distributors a bit. I eventually cornered the program director Nils-Erik Baehrendtz with his deputy Lars-Erik Kjellgren in the old Palais during MIP-TV and asked for a meeting. After having vented their frustration about the impossibility to acquire the Japanese titles from the Tokyo producers they suggested they would do business if I supported their Pippi Longstocking project to the tune of 900,000 Swedish crowns [US$1.3 million in today’s money]. I agreed and various deals were done. Back home I got into trouble because it turned out that SVT had seen every possible ARD station with the project and everybody had turned it down. But when the series and feature films finally were finished they become successes everywhere.”

By Dom Serafini

Audio Version (a DV Works service)

I wonder how he could have bought the rights to Bergmanns “Through A Glass Darkly” in Lyon 1963, when the film was released in Germany in 1962 already…