It was a big mistake to ask John Franklin Scott Laing, the founding general manager of the Los Angeles-based Rallie LLC, how he managed to speak five languages since he immediately embarked on a rollercoaster type of reply. “My mother was a constant traveler and lived in Italy, Spain, and Mexico. My father was a diplomat [the British Consul in New York and later at the U.N.]. The whole family was Francophone. When I was 12 I told my mother I wanted to learn German and she enrolled me in the [Goethe Institute], a German school outside Munich.”

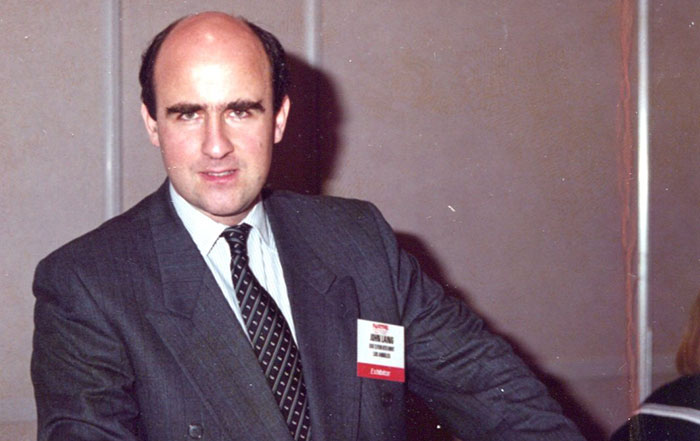

So it’s really no surprise that Laing would end up in the international TV business. He started out at Warner Bros. Television Distribution in 1983 at age 27, and later worked at Orion Pictures (in 1989), and at Rigel USA Inc. (in 1993). Now, he’s at Rallie, a company he founded in 2009.

In a 1990 sidebar article about Orion in the trade magazine Channels, Laing, then the president of the newly created division, Orion Television International, was described as someone who “crossed the Atlantic 18 times in his first year.”

The Orion story ended up being one of the last articles for the publication, which folded later that same year. Channels was founded by veteran industry journalist Les Brown in 1981, the same year that VideoAge was created. But contrary to VideoAge, Channels did not receive enough advertising support from the entertainment sector, and in 1985 was acquired by TV producer Norman Lear. Around 1990 Brown launched Television Business International, another trade publication with a name similar to VideoAge‘s subtitle: The Business Journal of Television. Brown died in 2013 at age 84.

But that was not the only time that Laing’s name was associated with a publication linked to VideoAge. Around 1990, Paolo Glisenti, then the head of Italy’s RCS Video, a multi-million dollar company backed by FIAT’s Agnelli family, apparently decided to compete with VideAge by financing Moving Pictures, a small trade publication in the U.K., which, after going through several ownership changes and relaunches, finally closed in 2012. More on Glisenti and Laing is coming up.

The year 1990 was also when Orion signed a $175 million deal with Columbia Pictures for handling the international distribution for Orion’s film and TV projects. However, Laing explained that, “it was for film and video only. That’s when I launched a new, separate division — Orion TV International.” He would go on to commute between Orion’s offices in New York City and Century City in Los Angeles in order to run the division. It is still unclear what the roles of Edward K. Cooper (in 1986) and Ernst Goldschmidt (in 1987) were. They were listed by VideoAge as running Orion’s International TV Sales from New York City. But according to Laing they were involved with Orion’s movies before the Columbia deal.

At Orion, Laing became acquainted with RoboCop, a 1987 movie later turned into a 1994 TV series. But let’s proceed chronologically.

When Laing started at Warner Bros., his traveling was limited to the U.S. He’d moved to Warner Bros. from a job at the Book Club division of Germany’s Bertelsmann in Chicago. Before that he worked as a freelance photojournalist for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Playboy, living in New Haven, Connecticut. And before that, when he was just out of Yale University, where he studied French literature, he sold door-to-door personal-care products for Combe Chemical.

The young Laing was quickly educated in the art of television at Warner’s offices in Chicago. There he learned how to read Nielsen and Arbitron ratings. After three months he was ready to hit the road and was dispatched to Green Bay, Wisconsin; Rockford, Illinois; and Davenport, Michigan to renew Warner’s shows at local TV stations. In his first outing, Laing, apologizing for his foreign (British) accent, managed to renew the shows and brought in $1.5 million. Before that, Warner’s TV sales in the Midwest were less than $950,000 a year. He now recalls that what helped him was the fact that he really didn’t know the business well, and instead of negotiating an “ask and a take price,” as was the traditional practice, he only based the negotiations on the “take price,” which he got. After two years of eating hamburgers in small Midwestern cities where fast-food eateries reigned supreme, Laing was transferred to Warner Bros.’ headquarters in Burbank, California.

It was 1985 when he first encountered “the man,” a.k.a. Charles D. McGregor, Warner Bros.’ top gun for worldwide TV distribution. But before we delve into that meeting, let’s digress. VideoAge began to publish the industry’s only Who’s Who of International TV Distributors in 1983, but McGregor refused to be listed until its 1986 edition, and in that edition he did not include Laing. He didn’t add Laing until the 1987 Who’s Who edition, and still Laing and other sales executives were never invited to the Villa that McGregor had Warner buy in Acapulco, Mexico, where he entertained content buyers. “But I took the Warner jet once to fly to NATPE in New Orleans,” Laing enthused.

Now back to Laing’s first encounter with “the man.” It wasn’t an example of cordiality, with invectives such as “What makes you think you can sell?” thrown at him by the veteran. However, it helped that McGregor knew Laing’s brother-in-law, the late Joe Antelo, who was married to his sister, and who produced the At The Movies program for the Tribune Company.

McGregor did not talk to or particularly like the press, even though he had a soft spot for this reporter’s former boss Sol Paul and for the September 1976 edition of Paul’s Television/Radio Age, he even gave an interview to Paul about international sales when he was the executive vice president of Worldwide Distribution at Warner Bros. Television. It was probably because of this aversion to the press that McGregor was not included in guides such as the International Television & Video Almanac and the revered Les Brown’s Encyclopedia of Television, which included other executives, such as the late Jim Marrinan when he was a VP at ITC TV distribution in Los Angeles.

Unlike many other U.S. studio executives, McGregor never took a stand at MIP-TV, yet opportunistically took advantage of the cluster of buyers in Cannes by renting nearby hotel rooms to conduct business. But he rented a suite at the Loews Hotel, the venue for the Monte Carlo TV Market. However, he’d refuse to have Luciana Paluzzi, who at that time was working as an Acquisition consultant for Silvio Berlusconi’s TV networks, in meetings because the Italian-born former actress was married to Michael J. Solomon, who served as chairman of Telepictures first, then as president of Lorimar-Telepictures.

Not an easy person to deal with, the diminutive McGregor had joined Warner Bros. in 1961, when he was 34 years old. Fifteen years later he was appointed president of Worldwide TV Distribution. Laing recalled: “Charlie had so much power at Warner Bros. He reported directly to Steve Ross, the studio’s CEO, because he generated lots of cash from TV licensing.” McGregor left Warner Bros. in 1989, when the studio acquired Lorimar-Telepictures, and Solomon became president of International TV Sales, and Dick Robertson became president of Domestic TV Distribution. That same year, Laing left Warner Bros. to join Orion. McGregor died in 2011 at age 84.

While based in Burbank, Laing returned to crisscrossing the globe, his calling in life. Earlier we left him traveling with his mother, but skipped a good chunk of his travelogue. Laing was born in Belgium, but moved to New York City when he was two years old.

At age four he moved to Helsinki with his mother, and then to Nassau, in the Bahamas. Four years later he was sent to the Harrow boarding school in the U.K., and it was then, at age eight, that he learned how to travel on his own, flying to Bermuda-Nassau and back to London for school. After high school, before starting at Yale in 1975, he first attended the University of Vienna for one summer, and then traveled to Geelong, a city southwest of Melbourne, Australia, where he formed a rock band and served as its lead singer. According to Laing, the band “was good during rehearsals, but not as much on stage!”

When Orion entered Laing’s life in 1989, the studio, founded in 1978 as a joint venture between Warner Bros. and four former executives at United Artists, was having great success. In 1982 it had severed its distribution ties with Warner and acquired Filmways, a studio based in New York City (where The Godfather’s filming was done). A year later Orion started a television production division that churned out shows such as Cagney & Lacey. In 1987 the studio produced the first moneymaking RoboCop movie. The following year, Metromedia’s John W. Kluge took full control of Orion (with a 67 percent stock ownership) after a battle with National Amusement’s Sumner Redstone, who had secured a 26 percent stake in it before taking over Viacom. Meanwhile, Laing was having great success with international TV sales aided by some luck when he found his former associates from Bertelsmann in Chicago now in Germany at Bertelsmann’s RTL.

Bertelsmann started as a shareholder of RTL, a free-to-air TV station based in Luxembourg, when it began in 1984 as RTL-Plus. In 1988 the TV station moved to Cologne, Germany, and in 1997 Bertelsmann merged its UFA, a film company acquired in 1964, with CLT, the corporate owner of RTL, to form CLT-UFA.

By 1990 RTL was already viewed as a major competitor by other German media companies, and Laing’s relationship with Bertelsmann was problematic, especially for the Kirch Group, which, through its U.S. rep, the very influential Klaus Hallig (1938-2013), went as far as supporting Laing when he founded Rigel, so that he didn’t need to return to work at any other U.S. studio important to the Kirch Group.

The ceiling came crashing down in 1991 when Orion filed Chapter 11 (reorganization bankruptcy) due to a slew of theatrical failures and no new network shows. Here’s how Laing recalls it: “I was in Tokyo and had just negotiated a $30 million all-cash deal with Mitsubishi, but had to pay my own hotel bill as my corporate Amex card was denied.”

The same year Laing’s contract expired in 1992, he accepted the position of chairman of Orion Pictures International, while the studio was negotiating new financing, first with Allen & Co., and later, with Goldman Sachs. Following corporate changes at Orion, Laing passed on a job at MGM to become CEO at Italy’s RCS Video, reporting to Paolo Glisenti, and he moved to Rome, renting an apartment that was just a 15-minute drive from the company’s offices. However, Glisenti refused to sign the final employment contract, and Laing took RCS Video to court in Milan and won a $200,000 settlement. That experience was recorded in a February 1993 article in VideoAge: “RCS Video: An Enigma Inside a Puzzle.” Coincidentally, the founder of the Italian law firm that represented Laing, Studio Cerulli-Irelli, was from Teramo-Giulianova, the same Italian town that this reporter hails from.

Three years earlier, Glisenti’s RCS Video (later RCS Film & TV), which Italy’s Linkiesta Magazine labeled as “antipatico” (unpleasant) in 2018, financed the launch of what became a perennial money-losing trade publication Moving Pictures. But it was not strategic for a company, such as RCS Video, which was already losing a $78 million investment into Carolco Pictures. After some other costly Hollywood mishaps, Glisenti left RCS Film & TV in 1994, and a year later it folded with losses of $150 million.

With the Italian job (no pun intended) gone, Laing leveraged his “true love,” RoboCop, to launch Rigel in 1993. And here is another Laing-esque story.

RoboCop: The Series was initially produced in 1994 when Canada’s SkyVision Entertainment paid $500,000 for the rights. Ultimately, 23 episodes (a two-hour pilot and 21 one-hour episodes) were made. Laing orchestrated that deal by persuading senior executives at Metromedia (Orion’s corporate owner), who controlled the property, to let him buy the TV series rights to RoboCop, which they did.

Coming to Laing’s aide was Silvia Kessel, the much feared Metromedia CFO, who trusted Laing’s advice since he’d earlier delivered on a past due and much needed $28 million balance expected from Italy’s Cecchi-Gori Group for a $35 million movie licensing deal. Using his dry British humor, Laing was even allowed at meetings to salute Kessel with “What are you stirring in your cauldron, today?” It usually elicited a cackle from her, being in an era when having a sense of humor was not a crime.

In turn Laing partnered with SkyVision, which arranged for the funding to produce the TV series. SkyVision then partnered with Rysher Entertainment, which put up $575,000 against domestic (U.S.) distribution rights for a 12-year period. Laing retained international rights through Rigel, a company he formed in 1993. Rigel held international rights only as a SkyVision agent. However, if ownership of SkyVision changed, Rigel had first rights to acquire the RoboCop series.

In 1996, SkyVision was sold to Jay Firestone’s Fireworks Entertainment. In 1997 Canwest Global purchased Fireworks. In 2005, Content Film acquired Canwest Global. In 2017, Kew Media bought Content Film. And, ultimately in 2020, Kew Media’s library was sold to Quiver Entertainment, which allowed Rigel to acquire the worldwide rights to the RoboCop TV series for mid six figures.

In 2020, Laing’s new company, Rallie, re-mastered all 23 episodes in a 16 x 9 HD format. On a side note, Canada’s Jay Firestone, whose company, Fireworks, bought SkyVision’s assets, helped Laing in 1996 to finance the distribution rights of Pacific Blue, Rigel’s first big TV series, which was produced by North Hall Productions.

Interestingly, MGM, which acquired Orion in 1997, only retained RoboCop’s trademark and its IP, but not the series, the three theatrical films, or the four TV movies, which are now controlled by Quiver Entertainment.

(By Dom Serafini)

Audio Version (a DV Works service)

Leave A Comment