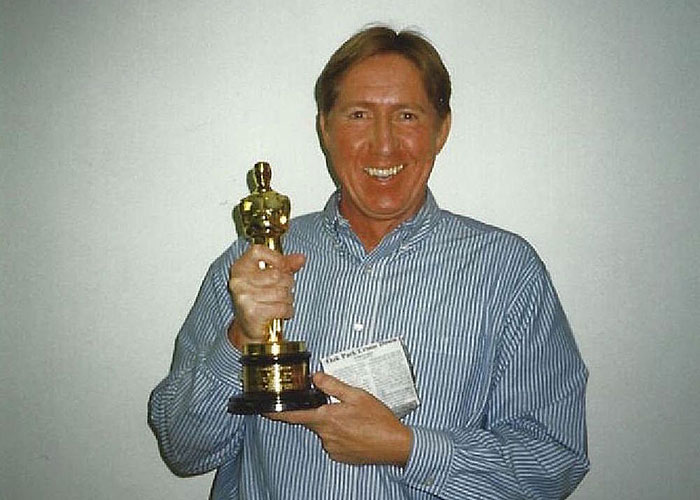

Tony Friscia is the “father” of the “ultimates,” a tool to guide content sales for the U.S. studios. His contribution was making the distribution business into… a business. Throughout his 43-year career, Friscia worked for eight studios. Since 2005, he’s run his own company. His ability to dissect content into tiny fragments, and then assign them dollar values, helped the studios maximize sales for their shows. The “ultimates” are where complex studio production contracts began to take real form.

The “ultimates,” a peculiar U.S. studio accounting procedure required since the 1980s by the non-profit Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) — which was established in 1973 to regulate accounting practices in the U.S. — almost got Anthony (Tony) Douglas Friscia killed.

Here’s how Friscia recalled it: “In 1987, I started working at Lorimar-Telepictures Corporation as vice president, Financial Planning, Home Video Division, reporting to the company’s CFO. As an expert on the ‘ultimates,’ I was asked to prepare a financial report on current and future sales of the company’s content rights. Just looking at Lorimar’s exploitation rights spreadsheet, I immediately sensed that they were all wrong. Of all their home video programs, the only one that was making money was Jane Fonda’s Workout tape. I showed the huge losses I discovered to my CFO who, in turn, reported [them] to Jerry Gottlieb, the division’s CEO.”

He continued: “I was seated at my desk with my back facing the door when I felt someone trying to strangle me. It was Gottlieb! [He] wanted to kill me for putting the company in such a dire predicament.” Friscia further explained that “at that time, the company was going through a scandal with the resignation of some of its top-level executives. It couldn’t afford another setback.”

According to the Los Angeles Times, the losses amounted to some $254 million. “News of the huge losses reached Lorimar’s co-founder, Merv Adelson, who in 1988 approached his friend, Warner Communications’ CEO Steve Ross,” and simply said: “Buy us out,” recalled Friscia. “In January 1989, Lorimar-Telepictures became part of Warner Bros.”

The stock transaction was valued at $1.21 billion, which included $660 million in Warner’s shares and the assumption of $550 million in Lorimar debt.

But this wasn’t the only “close call” for Friscia, for whom the “ultimates” became his ultimate challenge. “Everywhere I went their ‘ultimates’ were a mess,” he said in a telephone interview from his base in Oak Park, California.

Through his unique ability to dissect films and TV shows into tiny fragments, only to then assign them dollar values, Friscia helped the studios and producers maximize sales for their shows.

The “ultimates,” are also where complex (and fairly abstract) U.S. studio production contracts began to take real form that translated into actual dollars.

After completing his MBA at New York’s St. John’s University in 1975 at the age of 27, Friscia was quickly snapped up by Viacom in his native New York City. But it wasn’t until he left Viacom in 1978 and joined 20th Century Fox in Los Angeles that he first came “face-to-face” with the “ultimates.”

His final “confrontation” with the “ultimates” was in 1998 when he left his position as vice president, International Finance at Orion Pictures to become VP of Free Television Contract Administration at Warner Bros. International Television.

In 2002, while still at Warner Bros., he took the time to acquire his dual U.S.-Italian citizenship, leveraging the fact that his grandfather, Antonino, was born in Sicily, and only emigrated to the U.S. in 1912. Friscia’s mother was also European, having been born in Scotland. It is interesting to note that while Friscia is considered the “Father of the ultimates,” an earlier Italian, Luca Pacioli (1447-1517) from Tuscany, is recognized as the “Father of accounting.”

Later, Friscia’s two children, Lauren and Ryan, also acquired dual citizenship, and went to Italy for their MBA degrees at the Rome campus of St. John’s University. Lauren, now 35, is director, Marketing at Tapjoy, an Internet marketing service in San Francisco. Ryan, now 32, is VP, Finance and Operations at Bloom Media, a film production, sales, and financing company in Beverly Hills.

Since 2005, Friscia has been running his own consulting company, assisting U.S. and international entertainment companies.

Throughout his career in the entertainment industry, Friscia worked for a total of eight U.S. studios — including two stints for 20th Century Fox. The first was from 1978 to 1985. The second was from 1992 to 1996.

The first time the “ultimates” took Friscia to task was during his initial tour at Fox. At the time, he reported to Burt Morrison, who was directly under Alan Ladd Jr., president, Fox Theatrical.

Herb Lazarus, who worked at Fox until 1971, recalled Morrison as a “great guy,” a conscientious fellow who would question every expense report from salespeople. However, Lazarus acknowledged that at Fox (and later, at Columbia), there was little contact between sales and accounting. “Our sales contracts went to legal, and they dealt with accounting,” he explained.

Friscia further clarified that international sales executives were only concerned with library shows (which were not reviewed in the “ultimates”) because they could trigger payments to various guilds (or unions) that would exceed the license fees. In certain instances, residuals or participation fees could make a show unsellable.

The “ultimates” only covered new content, and projected finances for TV shows for 12 to 14 years, and for theatrical movies, for up to four years.

In 1981, Marvin Davis (in partnership with financier Marc Rich) took control of 20th Century Fox by buying shares on the stock market for $722 million. He borrowed heavily, taking out a $550 million loan from the Continental Illinois National Bank, putting in only $55 million of his own money. In 1984, after Rich had become a fugitive from justice for failing to pay $48 million in U.S. taxes (among other criminal charges), and Fox’s financial situation was precarious, with the company owing $600 million, the lending banks asked for a seven-year business plan, which Friscia prepared.

Once the “ultimates” were presented to the banks, they rejected Friscia’s plan. At this point, recalled Friscia, “My boss called me in and said: ‘We need a couple million dollars more.’ Not wanting to inflate revenues, I simply canceled several TV series, and thus I eliminated huge deficits. In effect, I got more by giving less, and the banks approved the new plan.”

In 1985, Davis sold his remaining Fox shares to Rupert Murdoch, and Friscia moved to Columbia Pictures, working under Herman Rush. At Columbia, Friscia became involved with another “ultimates” by-product — determining the value of the future shares of the 1975 to 1982 Barney Miller TV series for the show’s producer, Danny Arnold. At Columbia, however, they were called “clearances,” a term that Friscia disliked.

Here’s how Friscia explained it: “Arnold thought Columbia TV was not maximizing the full value of the show in syndication, and thus, his share of the profits. During the negotiations, Rush and I met with Arnold, and I subsequently valued Arnold’s share of the series at $35 million. However, Coca Cola, Columbia’s parent company, settled for what Arnold demanded: $50 million for complete ownership. Reportedly, when Rush left Columbia, his replacement, Barry Thurston, wrote down [or reduced the asset of] the $50 million settlement to $35 million.”

Friscia got closer to the “ultimates” again at his second stint at 20th Century Fox in 1992, this time as a consultant for the group’s International TV division. He was brought on board by Len Grossi, then an EVP. At that time, Fox was headed by Lucie Salhany, who left Paramount in 1991 to become Fox’s CEO.

Friscia had met Grossi just before Friscia was terminating his first stint at Fox.

When Grossi was CEO of Metromedia Producers Corp., Friscia interviewed with him for a financial position. He was told that Grossi always had black jelly beans nearby.

Friscia recalled: “I called Grossi to set up the interview. It was around 1985, when I was leaving Fox. I prepared for the interview by purchasing a jar of Jelly Belly jelly beans to give him as a gift. The bribe worked, he offered me the job. (Many still joke that that is where the expression “bean counters” comes from.)

“But, at the same time, I was offered a position at Columbia Television. I did not know much about Metromedia, but I did know that Columbia was a full-fledged studio. So I took the offer from Columbia.”

A few years later, after Friscia left Columbia due to the reorganization by Embassy/Coca Cola, he had lunch with Grossi in the Fox commissary. As they looked back, the talk was that, had Friscia accepted the Metromedia position, he would have wound up back at Fox given the acquisition of Metromedia by Fox in 1986.

In 1994, Salhany moved back to Paramount to launch the United Paramount Network, which later merged with The WB and is known today as The CW. Salhany took Grossi with her. In 2015, Friscia joined Grossi’s Baseline Media & Entertainment to form a new content marketing company: Media Content Group, which provides library and privately-owned intellectual property representation, legal consulting, and expert witnesses.

In his career as a consultant, Friscia also evaluated the Weintraub Entertainment Group library in London, consulted with France’s M6 for a potential acquisition, met with Mexico’s Televisa to evaluate a television series for seven participants, and checked in with NBC to prepare participation statements for Saturday Night Live.

These activities were in addition to time spent serving as a trial witness in the litigation between producer Alan Ladd, Jr. and Warner Bros., and representing Rocky producers in a potentially litigious situation with MGM, which resulted in an out-of-court settlement.

When Friscia got involved with the “ultimates” in 1978, companies did not yet have office computers, and, in order to automate the process, which was officialized by the FASB in 1981, it was necessary to rent computer time. “At Fox we had a terminal in our office and were charged by a Century City company for the time-sharing by the minute,” recalled Friscia.

At that time, the industry was dealing with just five rights: Theatrical, non-theatrical, network TV, domestic syndication, and international. In the years that followed, the number of windows grew at a slow, but steady pace until the turn of the century, when they exploded, reaching today’s 80-plus rights (which was reported in VideoAge’s May 2017 Issue). “However,” said Friscia, “the number of rights is not the hard part. The calculation of the participants’ share is the most difficult part.”

He explained further: “A participant can be a writer who could get a 2.5 percent share and some ‘ultimates’ can have several participants, including stars, producers, directors, investors, etc. And there can be different participation definitions for each participant like ‘gross,’ ‘adjusted gross,’ ‘modified adjusted gross,’ ‘net profit,’ etc. In addition, each participant gets an individual participation statement.”

As far as license fee increases were concerned, the changes, according to Friscia, were mostly due to escalating production costs.

“When I joined Fox under Salhany, I discovered that everything in their international license agreements was wrong,” he said. “The license fees and the number of runs were not entered in the computers, [thereby inviting] potential lawsuits because the same picture could be sold twice. Plus, availability was not entered correctly. This could have affected sales. It was just a mess. And my job was to find the errors and have them corrected for thousands of contracts.”

Friscia found the same situation when he moved to Orion Pictures, serving as VP, International Finance, in 1997, reporting to Sandra Gong, the company’s VP and controller.

At Orion, Friscia said he “joined right during the ‘gap’ between the ‘old Orion and the new Orion.’ The old Orion won four Oscars in eight years, but was run as an amateurish operation.”

Then, in 1997, just before Metromedia’s John Kluge sold Orion to MGM, “I discovered that all of Orion’s ‘ultimates’ were useless — all 675 of them,” he recalled.

Friscia hasn’t participated at any international trade shows other than the Santa Monica, California-based American Film Market. However, he’s one of the original cast of the L.A. Screenings’ Veterans’ Luncheon, which is held annually at the InterContinental Hotel (formerly the Park Hyatt).

The luncheon started in 2005 as an informal event attended by the late Jim Marrinan (then a TV consultant), Gary Marenzi (who had just left Paramount), and this VideoAge editor. The following year, it included Friscia, who had by then left Warner Bros. In subsequent years, Friscia coordinated the event, which at one point was attended by over 25 veteran TV executives.

(By Dom Serafini)

Audio Version (a DV Works service)

Leave A Comment