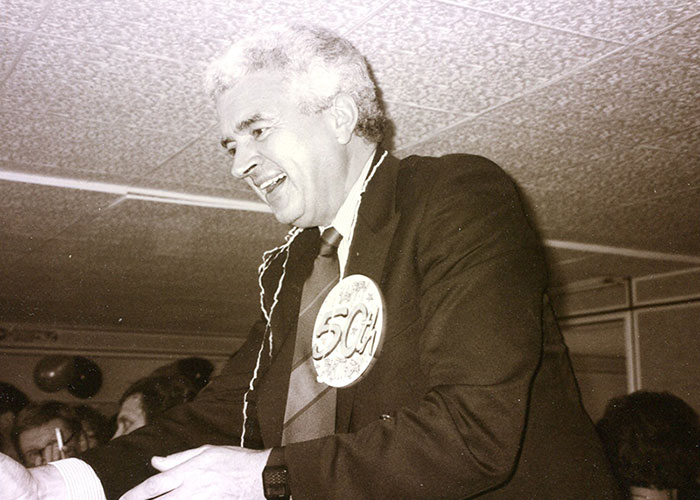

This writer’s first real encounter with William (Bill) John Peck occurred at MIPCOM 1993, when Peck asked him to send his photographer to take photos at his “surprise” 50th birthday party. VideoAge’s previous contact with Peck was three years earlier to coordinate taking a photo with his boss, Bert Cohen, for its MIPCOM Daily.

At the time of the party, Peck was managing director of Worldvision Enterprises’ U.K. offices and, later, in 1997, he became vice president, European Sales, also in London. Worldvision was then the largest American independent distributor with offices in four U.S. cities and five countries.

From almost its inception, Worldvision was also one of VideoAge’s (and other TV trade publications’) largest advertisers. For example, at that particular MIPCOM, Worldvision ran five ad pages in VideoAge Daily.

So when Peck “invited” VideoAge to his birthday bash at Mekong — a restaurant near the Grand Hotel he stayed in when in Cannes (a hotel he continues to patronize) — it could not have been refused. Actually, the “invitation” was accepted with pleasure knowing that Worldvision’s brass would be in attendance, including Cohen, who among VideoAge’s journalists was known as “make me look good Bert,” for his traditional warnings after interviews.

The birthday celebration was on a Monday night, after hours for VideoAge’s freelance photographer, so this writer had to “volunteer” to take the photos scheduled for the Wednesday Daily. Once the job was done, and just as the guests were ready for dinner, unceremoniously, Peck, with his trademark smile, asked him to leave.

Subsequently, the VideoAge Daily report featured three photos of the evening and noted that “about 50 guests were present, mostly buyers from the U.K., Scandinavia and Eastern Europe.”

This is how Peck described himself, when, for this feature 24 years after that birthday party, he was asked if there were any funny recollections in his 56-year career in the television business: “I doubt there are any funny anecdotes,” he said, “sorry, but I am not really a funny guy.”

But even if he’s not “funny,” Peck has a demeanor that renders him “simpatico,” and he’s always with a ready smile. And, even though he doesn’t smoke through an eccentrically Franklin D. Roosevelt-style long cigarette holder any longer, he still joyously plays piano at every occasion. “Who does anymore?” he said about no longer being a smoker, and added, “you remember my Korean ginseng cigarette holders?”

As far as playing the piano, Peck started at age six. “I was very talented,” he commented, “but I gave it up as a teen. Fortunately, I can still fumble along. At the Grand Hotel they bought especially for me (I think) a Yamaha grand piano and with Marjie Woods as a singer, we’re now the number one late-night [event] on the Croisette.”

In addition, looking through his extensive biography, one can’t help grinning, especially when picturing Peck attending his first MIP-TV in 1969. Here’s how he recalled it: “I drove to Cannes with Roy Gibbs (a colleague from Richard Price Television Associates [RPTA]) in a London Weekend Television van stuffed to the brim with video equipment — TV monitors, film projectors, loudspeakers and hours and hours of programs on videocassettes and 16 mm film — [because] RPTA was the first exhibitor to have screening facilities on its own stand.”

Another anecdote is recounted by Cohen, Peck’s former boss at Worldvision: “I remember visiting him in his hotel room one day, and found him standing on his head, which I eventually discovered, he did every day. Something about being healthy, he explained. Oh well…”

How Peck ended up at RPTA is described in his resume: At age 18, in 1961, rather than going to college he found a job at the BBC as a film dispatcher, and soon after was promoted to film librarian. In 1964 he joined Granada’s program sales and four years later he went back to the BBC as program sales assistant. But the BBC was not in the cards, because just 10 months later he accepted an offer from the nascent London Weekend Television (LWT) as international program sales executive. This job lasted six years, until 1974 when he joined LWT’s exclusive program sales agent, RPTA, as general manager.

Subsequently, and in the same year, starting in 1980, Peck jumped to Time-Life Television, Novacom and then to King Features, all as head of program sales and all in London. Here is how he explained it: “When Time-Life Television closed down (its film and TV catalog was sold to Columbia), two top Time-Life executives asked me to join Novacom, their new company dedicated to selling Boston’s WGBH TV product internationally, in particular the Nova documentary series. A couple of months later, Novacom was acquired by King Features.”

In 1982 Peck joined Worldvision where he remained for 18 years until the company was taken over by Paramount Television.

Here is how Cohen remembered offering him a job: “I first met Bill at the Caribbean Film Market, being held in Paramaribo, Suriname. I knew then that I would like to work with him.”

However, Cohen’s recollection differs somewhat from that of Peck, who also added a funny account. “Actually,” said Peck, “the first time Bert and I met was at the first Caribbean Film & TV Market, held the year before in Barbados in July 1975, but we didn’t really connect then. It was indeed in Suriname that we met properly, and a funny incident was at a dinner that some of the distributors went to at an Indonesian restaurant in downtown Paramaribo.

“We had entrusted Bert with the task of paying the bill after we had all made our cash contributions to him. I remember Bert clutching a huge fistful of Suriname guilders in one hand, and the dinner bill for all of us in the other and looking totally bewildered. He started counting out the cash, note by note and was doing quite well until he got to a two and a half guilder note, which threw his calculations out, and he had to start again. The process went on for quite a while, as the rest of us were laughing until we had a stomach cramp.”

Then Cohen continued: “When he came to Worldvision, he immediately became a major force for us in the U.K., Scandinavia, and Africa. I was amazed at how well he was thought of by the buyers and his peers. Bill was loved by everyone in the business. The personal relationships he had with his buyers were amazing and certainly gained him enormous trust, which translated into wonderful sales years, and lifetime friends.”

The Paramount “merger” in 2000 took Worldvision full circle, since it was created in 1954 by the ABC TV Network-Paramount company as ABC Films and, in 1959 it became Worldvision Enterprises, and as its president Henry G. Plitt, a former Paramount executive, was appointed.

With the advent of the Fin-Syn rule in 1971 (which prohibited TV networks from owning the programs they broadcast), Worldvision was spun off as an independent company and acquired by five former ABC Films executives in 1973.

Subsequently, Worldvision went through various ownerships (Taft Broadcasting and Great American Communications). In 1989 it was acquired by Spelling Entertainment, then a three-year-old public company, which eventually became 67 percent owned by Blockbuster. In 1994, Blockbuster merged with Viacom, which owned Paramount. Over the years, Viacom increased its Spelling stakes to 78 percent and in 1999 it paid $162 million to acquire the remaining 22 percent of Spelling.

Reportedly, due to a shortsighted bean-counter division, Worldvision’s brand (which was a gold mine), was absorbed by Paramount with the goal of saving 10 percent of operations costs, and in the process Paramount lost an estimated $80 million revenue, out of the $110 million that Worldvision generated, especially overseas.

Peck stayed with Paramount as consultant for one year and, later, as VP of European Regional Sales up until 2005, when he started his own consultancy company, which is still active with such clients as Italy’s Mediaset and Ukraine’s Star Media.

At one point, Peck was consulting 16 distribution companies from six countries, including Russia’s Channel One. “In the beginning,” he said, “there was only one: the Russian production company Amedia. A few months later, the managers at Russia’s Central Partnership asked me to represent them as well. My relationship with Central went back to 1994, when I sold Dallas to them. Then in 2006, Vlad Ryashin set up Star Media in Kiev and asked me to become a consultant for his company too,” he said.

Over the years, at least since VideoAge began following his career, Peck has not changed much, except, perhaps being nicer to this reporter. Even his still-dense head of hair is just as white as when VideoAge Daily first ran his photo at MIPCOM 1991. However, Peck pointed out that he was “not born with white hair. My hair was very dark at birth and continued to be so until, I guess, the 1970s. Blame the graying process on working for Bert!”

But his early graying was surely not caused by his boss, since he had “no real challenges to mention of, but perhaps a few set backs, like when in 1985 Worldvision was declared persona non-grata in the U.K., after it sold Dallas to Thames Television, with claims that Thames Television went behind the back of the BBC, the original U.K. broadcasters of the program,” he said.

Here is how Peck recalled the story: “We broke British broadcasting’s cozy system, whereby it was agreed that no broadcaster would poach a rival’s program.

“Dallas had been getting huge ratings for the BBC, a situation that was upsetting Thames Television. In 1983 Pat Mahoney (head of Program Acquisition at Thames TV) said to me, ‘Bill, before you renew the next season of Dallas with the BBC, talk to Thames.’ We needed a price increase every year due to spiraling production costs, and the BBC made it very tough. Early in 1984 Pat made me an offer of $60,000 per episode; the BBC was paying $41,000 and were prepared to offer just $42,500 for the next season. Thames also offered us a life-of-series commitment for all remaining seasons with a 10 percent price escalation per year.

“At NATPE 1984 in San Francisco, Bert met with Alan Howden, the BBC’s controller of Program Acquisition, and told him that we had received an offer for Dallas from ‘another U.K. broadcaster.’ Alan suspected he was bluffing to up the price, and telephoned Michael Grade, controller of BBC1. Grade assured Alan that this offer could not have come from ITV (of which Thames was a member), because he had spoken the previous day with Paul Fox, managing director of Yorkshire Television and head of the ITV Program Purchase Group, who had spent the previous afternoon with Bryan Cowgill, managing director of Thames. Cowgill had not mentioned Dallas to Fox.

“Cowgill and his controller of Programs, Muir Sutherland, had deliberately kept quiet about the offer. They also felt confident that they would persuade the rest of the ITV Network to take the series and were offering Worldvision full ITV Network rights. So, I took the contract to Mahoney to be signed by Cowgill and Sutherland.

“When the story was leaked to the press, the BBC cried foul. Thames Television was accused of double-dealing, and Worldvision was considered a company not to do business with.

“The Dallas saga even raised questions in the U.K. Parliament and went right up to the high court, where it was decided that the BBC get it back, but on the terms that Thames had offered us. Ultimately, Thames never showed a simple episode, and their contract was taken over by the BBC.

“Then, in 1985, while still persona non-grata in the U.K., Worldvision acquired the international rights of the miniseries The Key to Rebecca. I presented it to the ITV group at MIP in the same year, and Warren Breach, controller of Planning and Acquisition at London Weekend Television, said to me, ‘Bill, this is just what you need right now – a great new show. ITV is very interested.’ A couple of months later, I did the deal with ITV, and everyone was friends again!” Peck concluded.

One of Peck’s greatest career highlights was the 1991 invitation by Soviet Television to broadcast 20 hours of Worldvision programs during one week, which was viewed by an estimated 150 million people (the Soviet Union was dissolved early that year, but the TV network was still under the USSR Gosteleradio).

According to Peck, “that was the first time that so much airtime was devoted to on American TV series.” In exchange for the airtime, Worldvision received five minutes per hour, which was then sold to advertisers. At that time, Worldvision was owned by Carl H. Lindner Jr.’s Great American Communications, who had investments in Chiquita Bananas. Upon hearing of the Worldvision deal, Lindner acquired 15 minutes of air time for Chiquita in the hope of resurrecting his banana business in Russia. Recalled Peck: “Neither Bert nor I had any idea he had a banana business in the Soviet Union. In those years, the average Soviet had no idea what a banana looked like, let alone how it tasted!”

The other highlight was the $20 million deal with Channel 5 in 1997 just before it went on the air in the U.K.

And what about now? “Nowadays the distribution business is very complicated. In the past you could shake hands. Today in the contracts, just for the ‘catch-up’ rights there are five pages of definitions,” Peck conceded.

(By Dom Serafini)

Audio Version (a DV Works service)

Many congratulations !

What a delightful story about a highly talemted man.

It’s unusual to read about someone who works in, what sounds like rather a cut-throat industry who can dodge the bullets and still be held in high regard by everyone that he encounters.

Congratulations to Bill Peck who has achieved so much success in his field.

A LEGEND!

Congrats lovely Bill !! Xx

Great article, Congratulations, Bill. A true tribute to an extraordinary career.

Congratulations! This is amazing! :D

Congratulations for your career

Evelyne Pastré Riccione